Homeowners Insurance

Home, Volatile Homeowners

A look across nearly five decades of homeowners results shows a market that was never for the faint of heart.

- Lori Chordas

- November 2019

-

Key Points

- Hit Home: The U.S. homeowners insurance market continues to see a rise in insured losses from the growing spate of catastrophes in long-standing and new risk-prone areas.

- At the Doorstep: Insurers are relying on abundant reinsurance, alternative capital and sophisticated catastrophe modeling to help manage those exposures.

- Homeward Bound: Rising volatility in the market isn’t keeping homeowners from migrating to high-risk areas, including coastal states that continue to see more coverage moving into the hands of private insurers.

The U.S. homeowners market has been rocked by volatility over the years, driven largely by a barrage of natural catastrophes.

In 1971, the earliest year for which AM Best has digitized industry results, losses in the homeowners market hovered around $1.6 billion.

It’s challenging to eliminate volatility in the homeowners insurance market but insurers are counting on technology and data analytics to help them better price and manage risk, and achieve greater scale.

Richard Attanasio

AM Best

Insurers will be able to withstand future losses, “as long as they are able to reflect the true cost of providing coverage in their rates and that there are no more significant regulatory changes like what we saw in Florida after Hurricane Katrina and other events.”

Dr. Robert Hartwig

University of South Carolina

Last year, incurred losses climbed to more than $69 billion, largely fueled by another round of devastating weather-related property damage that, according to Munich Re, generated $52 billion in insured losses across various lines.

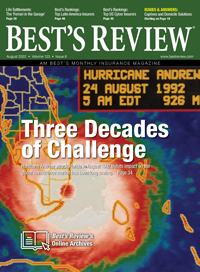

Over the last decade, U.S. hurricanes like Katrina, Ike, Michael, Rita, Sandy and Wilma grabbed national headlines and forced homeowners insurers to pull back from some U.S. coastal states or the market completely.

In a less dramatic fashion, other U.S. states and regions have often grappled with their own perils, including severe thunderstorms, hail, tornadoes, winter storms and flash floods.

States such as Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, Minnesota, Oklahoma and Tennessee experienced some relatively dramatic, periodic loss spikes caused by those perils.

A look at Colorado's 50-year loss history reads like an electrocardiogram. Annual incurred losses held around or below $500 million from 1971 to 2007 followed by a series of sporadic highs and lows that began to surge in 2008, according to AM Best. In 2018, incurred losses reached a near $3 billion record high, driven by events such as a May hailstorm in Denver that damaged homes, windows and roofs.

As homeowners insurers recover from those types of events, many are reevaluating their books of business in areas that have traditionally been considered less vulnerable to natural disasters, said Dan Friehs, executive vice president and client services practice leader for Marsh & McLennan Agency.

In America's Heartland, where Friehs lives, earthquake risk has forced some homeowners carriers out of the market. The midwestern United States hasn't suffered a catastrophic earthquake since dual 7.5-plus magnitude quakes struck Missouri in 1811, yet carriers aren't taking chances.

Friehs said insurers are examining their overall collective exposure to determine if they can preserve their balance sheets and pay claims in domestic markets in the event of a large quake or other calamity.

House of Cards

A 2011 tornado in Joplin, Missouri showed carriers' vulnerability to those exposures.

Three mutuals, Barton Mutual Insurance, Gateway Mutual Insurance and Cape Mutual Insurance, with collective premiums of $29 million, became insolvent after paying $48 million in combined claims from the storm that destroyed more than 7,000 homes.

Those losses came during a three-year period from 2010 to 2012, a time when U.S. coastal areas were enjoying relatively quiet hurricane seasons but many of the nation's interior states experienced an uptick in surprise cat losses.

Many insurers in those states responded by increasing rates, Dr. Robert Hartwig of the University of South Carolina said. Hartwig is a clinical associate professor in finance and the director for the Center for Risk and Uncertainty Management at the university's Darla Moore School of Business.

Several of those states today are home to some of the nation's highest homeowners insurance premium rates, including Oklahoma and Kansas, with the fourth and fifth highest rates, and Colorado rounding out the top 10, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

Rates in Oklahoma climbed more than any other state over the last 10 years, from an average premium of $1,054 in 2007 to $1,875 in 2016, according to the NAIC. During that period, 186 natural disasters were declared in Oklahoma, second-most in the nation behind California, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

In addition to raising rates, insurers continue to spread risk in other markets, turning to reinsurance, alternative capital and sophisticated cat modeling to better manage exposures. Those tools are putting coverage back into the hands of private insurers and depopulating many state-run insurance pools created to provide alternative coverage to citizens in high-risk areas, Hartwig said.

No Place Like Home

Volatility creates losses for homeowners insurers but it hasn't abated their risk appetite.

In 2018, overall premiums in the homeowners insurance market reached $99 billion. In 1971, that total stood at $3 billion, according to AM Best. Accounting for inflation, that $3 billion would be worth $19 billion today.

In Florida, more coverage is now written in the private sector than in the past decade, said Hartwig, similar to growth in wildfire-prone markets such as Colorado, Arizona and California.

Hurricanes and earthquakes were once considered the most severe homeowners risks, but wildfires have joined that lineup.

In 2018, homeowners insurers incurred nearly $13 billion in insured losses from California's most deadly and destructive wildfire season that saw 8,500 fires blaze across more than 1.89 million acres in the state, according to the California Department of Insurance.

Prior to that, AM Best reports, overall annual losses in the Golden State held steadily below $4 billion for more than four decades.

Widespread recent wildfires in California convinced some insurers to stop writing home coverage in the state while others opted not to renew policies in high-risk areas.

However, wildfires and other perils have not deterred insureds from building or moving to long-standing and new cat-prone areas.

Hartwig expects over the next several years new home construction in the United States will grow, along with increasing population migration to the southern and western United States in pursuit of economic opportunity.

To help alleviate increased risk, insurers will need to support stronger building codes and zoning ordinances in those areas, Hartwig said.

Coming Home

It's challenging to eliminate volatility in the homeowners insurance market but insurers are counting on technology and data analytics to help them better price and manage risk, and achieve greater scale, Richard Attanasio, a senior director at AM Best said.

Homeowners insurers have not adopted technology as quickly as many of their auto insurance counterparts. But Attanasio expects that homeowners insurers will continue to leverage technology through the use of sensors, alarms, various monitoring devices and other elements of the internet of things.

Some homeowners insurers are partnering with technology companies and startups to deploy smart home devices that monitor smoke, flames, water and other potential drivers of loss.

Carriers are also incentivizing insureds to use those devices, as well as employing artificial intelligence and predictive analytics in their own organizations to increase connectivity, improve customer experience and reduce costs, Attanasio said.

While technology will help mitigate and manage weather-related property losses, experts say it's only part of the solution.

That's because climate change is “real,” said Marsh & McLennan Agency's Friehs, who expects that changing weather patterns will continue to wreak havoc.

Annual inflation-adjusted homeowners insured losses in the 1980s hovered around $5 billion. Today, those losses top $35 billion, University of South Carolina's Hartwig said.

“You don't need a PhD in economics to figure out where this trend is going. There's no question that long-term trends of insurance cat losses are up, and the 2020s are unlikely to be any different than the prior four decades,” Hartwig said.

But Hartwig is optimistic that insurers will be able to withstand those losses, “as long as they are able to reflect the true cost of providing coverage in their rates and that there are no more significant regulatory changes like what we saw in Florida after Hurricane Katrina and other events.” One change in Florida included allowing greater use of “assignment of benefits,” which allowed contractors to remediate damaged properties ahead of insurers' oversight. That led to sharp increases in claims costs.

Carriers writing in noncoastal areas will need to focus on core underwriting discipline and improved enterprise risk management capabilities, said Maurice Thomas, a senior financial analyst at AM Best. That includes focusing on risk selection through enhanced modeling and mapping technologies, as well as recalibrating reinsurance programs to sustain long-term viability, he said.

This will allow insurers to better manage volatility from shock losses as well as ensure long-term stability in their earnings.

However, Thomas suggests that carriers with significant concentration and limited scale should maintain a sufficient level of risk-adjusted capitalization to offset volatility in their earnings due to unexpected catastrophic events.

As volatility rises, so do insurers' needs to continuously reevaluate existing and future market opportunities, Julie Rison, vice president of private client services at Marsh & McLennan Agency said.

“If carriers are going to pull out of the Florida or California market, for example, how long will they be able to do that? Eventually they'll have to return to the market. Insuring your home is a very personal thing, and if a carrier leaves the market or pushes people away, insureds may take offense and seek other options,” she said.

Hartwig remains optimistic about the future of the domestic home insurance market, which remains a profitable business, with relatively stable rates and healthy competition.

He expects direct premiums to grow $1 billion to $2 billion annually through a combination of upward rate trends and growth from new exposures.

Hartwig noted that market growth is tied to demographics that ultimately drive new exposures.

Hartwig also expects that private homeowners insurers will gain a greater stake in the flood insurance market by writing a greater share of coverage currently written by the National Flood Insurance Program.

“That's a Rubicon private insurers and reinsurers are now looking to cross, and we see that as a tremendous growth opportunity while at the same time allowing insurers to better understand the risks,” he said.

See Best's Rankings: U.S. Homeowners Multiple Peril 2018 Top Writers

House Divided

The past five decades have brought about changes in U.S. homeowners insurance, including an exodus by some of the market's largest writers, winnowed by consolidation, failures and withdrawals.

Companies such as Aetna, Continental, Fireman's Fund and more than a dozen others have shed their homeowners businesses to focus on other lines of insurance or left the scene, either closing their doors or merging out of existence, said Brian Sullivan, editor of Risk Information Inc.'s Property Insurance Report newsletter.

At the same time other companies like Progressive and Berkshire Hathaway's subsidiary Geico have changed the way they market and sell the product, opting to partner with affiliates rather than directly selling or underwriting the coverage themselves.

Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffet discussed that decision at this year's annual meeting of shareholders, saying volatility could cost the company to lose as much in one year as it made in the prior 24, and the “float isn't as large.”

Berkshire Hathaway wrote homeowners coverage until 1992 when Hurricane Andrew hit Florida, the Bahamas and Louisiana.

Geico and Progressive remain focused on their core business, auto insurance, which continues to generate more new premiums than any other property/casualty line, said Dr. Robert Hartwig, a clinical associate professor in finance and the director for the Center for Risk and Uncertainty Management at the University of South Carolina's Darla Moore School of Business.

Historically, private passenger auto has always been larger and more stable than homeowners, but he said the advent of autonomous vehicles over the next several decades could change that by driving down frequency and severity of losses and depleting premiums in the auto line.

That could open the door for new market entrants who will shift their attention from private passenger auto to homeowners in an attempt to retain their customer base.

For decades, State Farm has dominated the domestic homeowners insurance market, with more than $18 billion in direct premiums written in 2018, according to historical insurance data compiled by AM Best, beginning in 1971. Allstate, Liberty Mutual, USAA and Farmers round out the current top 5.

In 1971, a time when the market was far less concentrated, State Farm's share of the homeowners line was 8.03%. From there, market share showed a steady rise, reminiscent of the recent growth in auto insurance of Geico and Progressive. State Farm's share of the homeowners market peaked at 23% in 1997, Risk Information's Sullivan said.

In 2018, State Farm's share of the homeowners market stood at 18.46%, a level last seen in 1989. “However, that's still extraordinarily dominant and more than twice the size of second-ranked Allstate,” Sullivan said.

Allstate's share of the homeowners market has also followed an arc, peaking in 1990 at over 12%. Sullivan said the company's management grew less comfortable with the volatility of the homeowners sector. By steadily re-underwriting its book of business, Allstate reduced its market share back to 8.39% by 2018, almost the same as in 1976.

At the same time insurers such as Liberty Mutual and Farmers were growing their share of the market. Liberty Mutual was the biggest mover, rising from 1.25% in the early 1970s to 6.76% last year, according to AM Best.

Lori Chordas is a senior associate editor. She can be reached at lori.chordas@ambest.com.